Studying Sternberg’s views on intelligence – A brief overview of the three-fold view of intelligence (or triarchic intelligence)

Contact Leslie

In studying different views and theories on intelligence and creativity I have become a fan of the works of Dr. Robert J. Sternberg – his writings are quite prolific. While I confess I am intrigued by many alternative definitions of intelligence, what initially fascinated me about Dr. Sternberg’s early work in this area was that he not only describes three distinct subtheories or metacomponents, but he also takes into consideration how the varied aspects can be used and balanced.

One of Sternberg’s very succinct definitions of intelligence states:

“Intelligent behavior involves adapting to your environment, changing your environment, or selecting a better environment.”

If we look at his early work on reconceptualizing what intelligence is we can see that there is a close link to that of Aristotle’s ancient premise that intelligence is composed of three aspects theoretical, practical, and productive intelligence. In Sternberg’s view intelligence revolves around the interchange of analytical, practical, and creative aspects of the mind. He notes on many occasions that what most IQ tests measure is only the componential/analytical aspects in intelligence.

Over the course of his career Sternberg seems to be intrigued by the ways different people actually use their intelligence — the interplay of the varied “metacomponents.” He contends that what makes the difference in determining if one is smart depends on how folks use and balance their mental aptitudes. Early on, in describing these aptitudes Sternberg keyed in on our methods of mental self‑government, as well as how we balance and use them situationally. Thus in his view measuring intelligence not only entails assessing how much of a certain ability we each have, but also how we use and/or combine our abilities to solve problems or adapt to certain environments. In contrast to others’ descriptions of intelligence, the governmental model leads to the assessment of how intelligence is used, directed, or exploited. Two individuals of equal intelligence might use or combine metacomponents quite differently. It then might be the recombination, use or directed application of the metacomponents that could make one seem more intelligent or more successful than the other in tackling certain tasks.

(Summarized from: Sternberg, Robert (1988) The Triarchic Mind: A New Theory of Intelligence. NY: Viking Press.)

Metacomponent subtheories:

Componential intelligence (later know as analytical intelligence) This is the traditional notion of intelligence and includes:

- Abstract thinking & logical reasoning

- Verbal & mathematical skills

Experiential intelligence (later know as creative intelligence) This is creative thinking which uses:

- Divergent thinking (generating new ideas)

- Ability to deal with novel situations

Contextual intelligence (later know as practical intelligence) This could be termed “street smarts” and embraces:

- Ability to apply knowledge to the real world

- Ability to shape one’s environment; choose an environment

Key components from The Triarchic Mind:

Initially mental self‑government included 5 separate but interactive categories ‑ function, scope, form, plus levels and leanings.

Sternberg was at Yale University when he developed a concept of intelligence that equates to combinations of individual preferences from three levels of mental self-management. These three areas correspond with:

- Functions of governments of the mind,

- Stylistic preferences, and

- Forms of mental self-government.

Examples: As a combination a person might prefer legislative functions, internal variables and hierarchical habits of mental self-government; while another individual might prefer executive functions; external variables and anarchic habits of mental self-government, and so forth.

I. Functions of governments of the mind are:

- Legislative – creating, planning, imagining, and formulating.

- Executive – implementing and doing.

- Judicial – judging, evaluating, and comparing.

II. Scope – stylistic variables:

- Internal – by themselves

- External – collaboration

III. Forms of mental self-government:

- Monarchic people perform best when goals are singular. They deal best with one goal or need at a time.

- Hierarchic people can focus on multiple goals at once and recognize that all goals cannot be fulfilled equally. These people can prioritize goals easily.

- Oligarchic people deal with goals that are of equal weight well, but they have difficulty prioritizing goals of different weight.

- Anarchic people depart from form and precedent. Often they don’t like or understand the need for rules and regulations. These people operate without rules or structure, creating their own problem-solving techniques with insights that often easily break existing mindsets.

Levels and leanings were also initially part of this discussion.

Levels:

- Global ‑ Large, abstract issues.

- Local ‑ Concrete problems, practical issues.

Leanings:

- Conservative ‑ Adhere to existing rules.

- Progressive ‑ Advance beyond existing rules.

Sternberg’s discussions on intelligence are very different from a lot of others because he appears to think that other than a static score, intelligence is somewhat malleable and should take into consideration things like culture, gender, age, parenting style, personality, and schooling. In this context, intelligence can be manipulated by ones contexts and experiences and it might even be improved with practice. Some of his other views are just as surprising as he sees intelligence as the ability to cope with novelty and the purposeful adaptation to, selection of, and the shaping of real‑world environments relevant to one’s life and abilities.

Think about it:

On the surface many of Sternberg’s descriptions appear to equate to some of the aspects of personality type theory. For instance, it may be apparent to those who have studied some of Carl Jung’s work on personality preferences that Sternberg’s “scope variables” of internal and external might equate to preferences for either introversion or extraversion in Jungian typology. In this context, preferences for internal (introversion) or external (extraversion) mental operations might be accurately calculated on popular personality tests like the Myers-Briggs or Kiersey-Bates.

Looking at Sternberg’s other descriptors in the areas of “forms” and “functions”, see if you can find any other parallels between his descriptors and aspects of traditional personality typologies.

Also, in varied combinations (3 [functions] x 2 [scopes] x 4 [forms] = 24) Sternberg’s Triarchic Model would yield 24 different combinations for mental preferences. Within Sternberg’s patterns, see if you can categorize and profile your own mental preferences and those of others you know well.

Successful Intelligence:

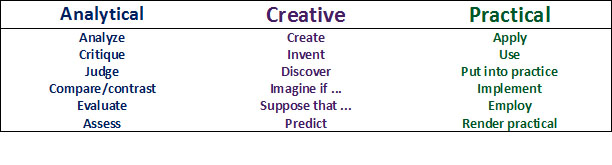

Many of the elements above were both expanded and yet simplified in his later work on Successful Intelligence. Here Sternberg contends that successful people learn to combine and use aspects from all three components of intelligence. Analytical forms comprise the ability to examine and include the mental steps or components that help one solve problems. Creative forms allow one to examine experiences in ways that offer insights and solutions. While the practical aspects of intelligence offer the ability to examine and adapt to the contexts and challenges of everyday life. In Successful Intelligence, Sternberg contends it is not enough to be proficient in just one area – there has to be interplay between all three forms of intelligence.

Sternberg spells out his definition of intelligence upfront when he says:

Successful intelligence is the kind of intelligence used to achieve important goals. People who succeed, whether by their own standards or by other people’s, are those who have managed to acquire, develop, and apply a full range of intellectual skills, rather than merely relying on the inert intelligence that schools so value. These individuals may or may not succeed on conventional test, but they have something in common that is much more important than high test scores. They know their strengths; they know their weaknesses. They capitalize on their strengths; they compensate for or correct their weaknesses.” (12)

Key functions in each aspect of intelligence:

Summarized highlights from Sternberg, R. J. (1997) Successful Intelligence: how practical and creative intelligence determine success in life. NY: Penguin/Putnam.

Summarized highlights from Sternberg, R. J. (1997) Successful Intelligence: how practical and creative intelligence determine success in life. NY: Penguin/Putnam.

Next Layer: The Kaleidoscope Project

Many avenues of psychology seem to have permeated, impacted and directed Sternberg’s research interests over the breadth of his career. (Observing and reading about his interests and related research keeps followers busy.) In addition to popularizing his theory of Successful Intelligence, or perhaps because of that concept, more recently he has also been fascinated with the concept of “wisdom.” As a strong advocate for alternative views of intelligence in 2010 Sternberg incorporated wisdom and his observations into it in a book on college admissions entitled College Admissions for the 21st Century . In this newer work he discusses his work on something called the Kaleidoscope Project which encourages updating college admission standards to go beyond traditional academic criteria and look at candidates adeptness at wisdom, creativity, and practicality. Sternberg believes the addition of these filters is a much better predictor of college GPA, success, and completion than conventional admission processes.

Sternberg, R. J. (2010) College admissions for the 21st Century. MA/Harvard University Press.

Sternberg discusses creativity and the Kaliediscope Project in this great article in the Chronicle of Higher Education.

Comments – A priceless list:

From: Why do intelligent people fail? (Sternberg, 1986) As you will see from this array many of these overlap into social and emotional intelligence, or have to do with the failure to find balance between Sternberg’s components of his Successful Intelligence – analytical, creative, and practical components.

1. Lack of Motivation: A talent is irrelevant if a person is not motivated to use it. Motivation may be external (for example, social approval) or internal (satisfaction from a job well done). External sources tend to be transient, while internal sources tend to produce more consistent performance.

2. Lack of Impulse Control: Habitual impulsiveness gets in the way of optimal performance. Some people do not bring their full intellectual resources to bear on a problem, but go with the first solution that pops into their heads.

3. Lack of perseverance and too much perseveration: Some people give up to easily, while others are unable to stop even when the quest will be fruitless.

4. Using the wrong abilities: People may not be using the right abilities for the tasks in which they are engaged.

5. Inability to translate thought into action: Some people seem buried in thought. They have good ideas but rarely seem able to do anything about them.

6. Lack of product orientation: some people seem more concerned about the process rather than the result of the activity.

7. Inability to complete tasks: For some people nothing ever draws to a close. Perhaps it’s a fear of what they would do next or fear of becoming hopelessly enmeshed in detail.

8. Failure to initiate: Still others are unwilling or unable to initiate a project. It may be indecision or fear of commitment.

9. Fear of Failure: People may not reach their intellectual performance because they avoid the really important challenges in life.

10. Procrastination. Some people are unable to act without pressure. They may also look for little things to do in order to put off the big ones.

11. Misattribution of blame. Some people always blame themselves for even the slightest mishap. Some always blame others.

12. Excessive self-pity: Some people spend more time feeling sorry for themselves than expending the effort necessary to overcome the problem.

13. Excessive dependency: Some people expect others to do for them what they ought to be doing for themselves.

14. Wallowing in personal difficulties: Some people let their personal difficulties interfere grossly with their work. During the course of life, one can expect some real joys and some real sorrows. Maintaining a proper perspective is difficult.

15. Distractibility and lack of concentration: Even some intelligent people have very short attention spans.

16. Spreading oneself too thin or too thick: Undertaking too many activities may result in none being completed on time. Undertaking too few can also result in missed opportunities and reduced levels of accomplishment.

17. Inability to delay gratification: Some people reward themselves and are rewarded by others for finishing small tasks, while avoiding bigger tasks that would earn them larger rewards.

18. Inability to see the forest through the trees: some people become obsessed with details and are either unwilling or unable to see or deal with the larger picture in the projects they undertake.

19. Lack of balance between critical/analytic thinking and creative/synthetic thinking: It is important for people to learn what kind of thinking is expected of them in each situation.

20. Too little or too much self-confidence: Lack of self- confidence can gnaw away at a person’s ability to get things done and may become a self-fulfilling prophecy. Conversely, individuals with too much self-confidence may not know when to admit they are wrong or in need of self-improvement.

________________________

Where is Sternberg now? After a series of administrative positions at Oklahoma State and the University of Wyoming, Dr. Sternberg is currently at Cornell University in the College of Human Ecology.

________________________

Want to know more about Sternberg’s theories and thoughts on intelligence? Sternberg is an extremely prolific scholar having penned over 1500 books, monographs, articles, and book chapters. Here are some book choices from Robert J. Sternberg, PhD:

- Beyond IQ: A Triarchic Theory of Human Intelligence

-

Successful Intelligence: How Practical and Creative Intelligence Determine Success in Life You can buy this classic for a penny!

-

Sternberg, R. J. and Grigorenko, E. L. (2007) Teaching for Successful Intelligence: To Increase Student Learning and Achievement 2nd Edition

- Wisdom, Intelligence, and Creativity Synthesized 1st Edition (2007)

- Sternberg, R.J.; Grigorenko, E. and Jarvin, L. (2015) Teaching for Wisdom, Intelligence, Creativity, and Success. Although the title of this book is similar to the previous one, this book deals with actually bringing these types of thinking into schools in a practical way.

Giving = Continued Sharing

I created the Second Principle to share information about the educational ideas at the heart of all good teaching. I am dedicated to the ideal that most of materials on this site remain free to individuals, and free of advertising. If you have found value in the information offered here, please consider becoming a patron through a PayPal donation to help defray hosting and operating costs. Thanks for your consideration, and blessings on your own journey.