©Leslie Owen Wilson (2020) Contact Leslie

A succinct discussion of older and selected newer taxonomies of learning.

A succinct discussion of older and selected newer taxonomies of learning.

Why do teachers need to know about and use taxonomies of learning? The answers are simple. First and foremost a taxonomy is a professional tool that helps educators craft instructional events that are meaningful to learners. Taxonomies of learning also provide specific frameworks for communicating to students and others what they are doing and why. In the long term these frameworks can be used to track instructional events over time. They can also be used as professional self-assessment tools allowing educators to reflectively see the patterns in their own teaching and instructional choices.

What is a taxonomy anyway? It is simply the science of listing and describing something. The intention of the concept was primarily that listings could be created to better organize large amounts of information. Often they are arranged hierarchically. That means that items are placed in some type of order – often one that ranges from simplest to more complex or vice versa. But a taxonomy can also be created to describe points below or above some described mid or neutral point. Or as with some of the newer taxonomies, they can be devised to indicate items at the same level, but ones in distinct categories.

Creating a taxonomy is a convenient method of organizing ideas in order to help learners, users, readers, or viewers more easily understand and remember a complex array of items, or a progression of elements or information. As indicated initially, using taxonomies of learning is also an effective way to help educators create exceptional instructional plans. They can easily help educators track what they are asking students to do to assure that lessons have variety and meet different learning tasks, needs and foci.

Three Domains of Learning – Classic Taxonomies of Learning:

There are three major, popular divisions of some of the older taxonomies of learning – cognitive, affective, and psychomotor. These emerged in the mid-fifties to the mid-seventies of the 20th century. However, it needs to be noted that there are also newer versions of taxonomies of learning that can be used to help plan, track or assess instructional events. Many of these hold exciting possibilities for both creating effective instruction, but also for actively engaging a broad array of learners. I will list some alternatives to the traditional classifications at the end of the main part of this discussion and include links to more in depth explanations and available resources.

Hint: If you find the continued use of the formal taxonomies of learning hard to remember, you can simplify the concept from cognitive, affective, and psychomotor to something more basic like head, heart, and hand (body) or mind, body, spirit if that is easier to remember.

The Cognitive Domain (1956 version, aka Bloom’s Taxonomy)

First described in our array of the most common three taxonomies of learning is that of the cognitive domain. This domain concerns how we come to know something, and how we construct knowledge. This taxonomy is more commonly referred to as Bloom’s Taxonomy (1956) as it was named after the first author listed in the array of authors that published this listing. Bloom’s Taxonomy describes the different levels of cognition which are listed from simple cognitive tasks to those which are more complex.

In the first table below I have listed not only the levels of cognition, but also companion performance verbs for each of the six designated levels. Many teachers loved this type of chart because when they were creating lessons it allowed them to pick and choose behavioral verbs for students’ performance tasks. Using this type of chart made it rather easy for teachers to create lesson plans by just plugging in the appropriate verbs. Using some of the verbs allowed them to actually see if learners had correctly accomplished a task thus making assessment more easily determined.

The downside: There are downsides to this ease of use. Unfortunately, many teachers did not chart students’ performances over time in order to make sure they were offering challenging tasks at different levels of cognition, or offering an intermix of tasks at varied levels. The other problem was when tasks were analyzed over time, performance assessments often found that teachers chose tasks at the lower levels of cognition much more frequently than those on more difficult or challenging levels. Regularly these selected levels were rote memory tasks or simple tasks requiring the acquisition of information or knowledge, or comprehension or application.

Unfortunately this deficiency in the diversity of instructional selections — ones stuck at lower levels — is often still a problem. There may be less obvious reasons for these limited instructional choices:

- Mirroring the old adage “they teach the way they were taught” some teachers often chose familiar tasks — ones that had been modeled by their former teachers, or ones they were good at in their own schooling. These choices may have been erroneously but easily justified because they closely mimicked common tasks from many teachers’ personal educational histories. Or

- Generally lower level cognitive tasks were/are easy to grade objectively. For instance, multiple choice, fill in the blank, or short answer tests are much easier and faster to grade than say an essay, a complex project, or a project that revolves around the completion of a multidimensional problem.

For a more complete in depth discussion of the original 3 domains and how they can be used, or for a complete discussion of the important 2001 revisions to Bloom’s taxonomy, read these linked pages. These linked discussions include suggestions and links as to how combining domains can be used to meet a broad range of learning styles, as well as used to create more complex, holistic, and memorable lessons.

The Cognitive Domain (1956, thinking or coming to know, this version includes performance verbs)

| 1. Knowledge: Remembering or retrieving previously learned material. Examples of verbs that relate to this function are: know, identify, relate, list, define, recall, memorize, repeat, record, name, recognize, acquire |

| 2. Comprehension: The ability to grasp or construct meaning from material. Examples of verbs that relate to this function are: restate, locate, report, recognize, explain, express, identify, discuss, describe, review, infer, Illustrate, interpret, conclude, represent, differentiate |

| 3. Application: The ability to use learned material, or to implement material in new and concrete situations. Examples of verbs that relate to this function are: apply, relate, develop, translate, use, operate, organize, employ, restructure, interpret, demonstrate, illustrate, practice, calculate, show, exhibit, dramatize |

| 4. Analysis: The ability to break down or distinguish the parts of material into its components so that its organizational structure may be better understood. Examples of verbs that relate to this function are: analyze, compare, probe, inquire, examine, contrast, categorize, differentiate, contrast, investigate, detect, survey, classify, deduce, experiment, scrutinize, discover, inspect, dissect, discriminate, separate |

| 5. Synthesis: (In the revised version of Bloom’s Taxonomy, now Creating #6) The ability to put parts together to form a coherent or unique new whole. Examples of verbs that relate to this function are: compose, produce, design, assemble, create, prepare, predict, modify, tell, plan, invent, formulate, collect, set up, generalize, document, combine, relate, propose, develop, arrange, construct, organize, originate, derive, write, propose |

| 6. Evaluation: (In the revised version of Bloom’s Taxonomy, this is now Evaluating #5) The ability to judge, check, and even critique the value of material for a given purpose. Examples of verbs that relate to this function are: judge, assess, compare, evaluate, conclude, measure, deduce, argue, decide, choose, rate, select, estimate, validate, consider appraise, value, criticize, infer |

Bloom, B.S. and Krathwohl, D. R., et al.(1956) Taxonomy of Educational Objectives: The Classification of Educational Goals, by a committee of college and university examiners. Handbook I: Cognitive Domain. NY, NY: Longmans, Green

***Again, this taxonomy was updated and revised in 2001, for an in depth discussion on these important update see this link.

The Affective Domain (1964)

Much of the work on describing and classifying taxonomies of learning came out of the University of Chicago in the mid 20th century from both Benjamin Bloom and his colleagues, and later from some of his students. The research findings and writings that emerged from this group of university professionals have and are paramount in shaping much of American education. David Krathwohl was one of Bloom’s colleagues engaged in writing about the cognitive domain and he is the primary author in describing the affective domain.

For the next step in defining how humans learn, Krathwohl conceptualized and created a taxonomy based on how individuals internalize knowledge and experiences through feelings and emotions (or the affect). According to Krathwhol internalization is the “process whereby a person’s affect toward an object passes from a general awareness level to a point where the affect is internalized and consistently guides or controls the person’s behavior.” For this taxonomy he described five levels of internalization as: receiving, responding, valuing, organization, and characterization.

Many educators in the math and the science areas think it is impossible to bring the affective domain into their teaching. That is simply not true! Anytime learners have an opportunity to plan and work cooperatively within an organized framework; anytime they are collectively or individually challenged to develop self-esteem through finding solutions to difficult problems; and anytime students are actively encouraged to self-reflectively examine or critique their performances, they are using the affective domain. If part of a teachers’ mission is to actively encourage self-confidence, independence, collaboration, and personal growth in students, then they can actively incorporate the affective domain into their instruction no matter what the subject area!

Effective teachers also know that the human brain via the limbic system responds to and remembers emotional triggers first. These teachers look for opportunities to connect their students to related stories with emotional threads, real life problems, issues that affect people’s lives, or personal insights related to their content in order to get and keep students engaged. Attention follows emotion.

Why not use aspects from the affective domain in tandem with actively engaging your students in their cognitive tasks? In the real world in order to be successful and happy, human interactions, and social and emotional learning is often as, or more, important than cognitive growth.

The Affective Domain (1964, feelings and emotional responses)

| 1. Receiving – refers to the learner’s sensitivity to the existence of stimuli – awareness, willingness to receive, or selected attention. feel, sense, capture, experience, pursue, attend, perceive |

| 2. Responding – refers to the learners’ active attention to stimuli and his/her motivation to learn – acquiescence, willing responses, or feelings of satisfaction. conform, allow, cooperate, contribute, enjoy, satisfy |

| 3. Valuing – refers to the learner’s beliefs and attitudes of worth – acceptance, preference, or commitment, especially as these may relate to value or ideal. believe, seek, justify, respect, search, persuade |

| 4. Organization – refers to the learner’s internalization of values and beliefs involving (1) the conceptualization of values; and (2) the organization of a value system. As values or beliefs become internalized, the leaner organizes them according to priority. examine, clarify, systematize, create, integrate |

| 5. Characterization – refers to the internalization of values. This is the learner’s highest level of internalization and relates to behavior that reflects (1) a generalized set of values; and (2) a characterization or a philosophy about life. At this level the learner is capable of practicing and acting on their values or beliefs. internalize, review, conclude, resolve, judge |

Krathwohl, D.R., Bloom, B.S., Masia, B.B. (1964). Taxonomy of Educational Objectives, the Classification of Educational Goals. Handbook II: Affective Domain. New York: David McKay Co., Inc. #ad

Psychomotor Domain- (1972 Harrow; 1972 Simpson; 1975 Dave )

The last domain to be explored, explained, and conceptualized was the psychomotor one. Its related taxonomy attempts to explain how we come to know something through observation and perception, varied levels of movement, physical mimicry, or embodied learning. Choices in this area are a bit more varied and complex because this domain has been defined by 3 different authors.

However, please note, many teacher training texts and teacher preparation programs in the United States seem to have gravitated to the psychomotor domain as described by Anita Harrow. Perhaps the reasons for this choice are both the completeness of her descriptions and the focus it places on writing related behavioral objectives. Using Harrow’s descriptive taxonomy helps teachers create formal plans that clearly communicate what they are trying to get students to learn, experience and achieve.

Harrow’s listing (1972)

| Harrow’s Levels |

| Reflex movements – Objectives at this level include reflexes that involve one segmental or reflexes of the spine and movements that may involve more than one segmented portion of the spine as intersegmental reflexes (e.g., involuntary muscle contraction). These movements are involuntary being either present at birth or emerging through maturation. |

| Fundamental movements – Objectives in this area refer to skills or movements or behaviors related to walking, running, jumping, pushing, pulling and manipulating. They are often components for more complex actions. |

| Perceptual abilities – Objectives in this area should address skills related to kinesthetic (bodily movements), visual, auditory, tactile (touch), or coordination abilities as they are related to the ability to take in information from the environment and react. |

| Physical abilities – Objectives in this area should be related to endurance, flexibility, agility, strength, reaction-response time or dexterity. |

| Skilled movements – Objectives in this area refer to skills and movements that must be learned for games, sports, dances, performances, or for the arts. |

| Nondiscursive communication – Objectives in this area refer to expressive movements through posture, gestures, facial expressions, and/or creative movements like those in mime or ballet. These movements refer to interpretative movements that communicate meaning without the aid of verbal commands or help. |

Harrow, A. (1972) A Taxonomy of Psychomotor Domain: A Guide for Developing Behavioral Objectives. New York: David McKay. #ad

Despite this preference for Harrow’s work by practicing professionals in the areas of physical education, there are two other taxonomies of the psychomotor domain.

Simpson’s Listing (1972)

| Simpson’s – Levels & Short definitions | Sample actions |

| Perception The ability to use sensory input or clues to guide motor activities. | Visually estimating the trajectory of a ball and responding to those cues. |

| Set The emotional, mental or physical mindset – the readiness to act in any of these three dispositions. | Anticipating performing with an instrument in relation to the actions of the conductor. |

| Guided Response At the beginning of learning a complex new skill — the imitation, trial and error. | Following instructions on a video or from an in-person demonstration. |

| Mechanism The middle portion of learning a complex skill or skilled movement. | Actually fixing or repairing something after trial and error. |

| Complex or Overt Response Skillful movements or imitation of physical movements that are complex. | Executing a dance that has multiple steps or complex patterns– foxtrot, salsa, rumba, electric slide, square dance, etc. |

| Adaptation Well-developed skills to the point where the learner/performer can make personal adjustments of modifications. | Responding to things that go wrong or ones that are unexpected. Like not having the right tools but modifying the ones one has in order to fix something. Or, a teacher changing or modifying instructional materials so it meets her students learning needs. |

| Origination Creating new movements or patterns | Creating a new training program or designing a new gymnastics routine or choreographing an original dance. |

Simpson E.J. (1972). The Classification of Educational Objectives in the Psychomotor Domain. Washington, DC: Gryphon House.

*For an excellent, more detailed explanation of Simpson’s Taxonomy in PDF format, one with action verbs and numerous examples, please see University of Connecticut’s pages on Simpson’s domain.

Dave’s Listing (1970, 1975)

The work of Ravindrakumar H. Dave in conceptualizing the psychomotor domain is much harder to track than that of either Harrow or Simpson. It appears in a conference paper from 1967, and then again it is cited in a collection printed with publication dates of both 1970 and 1975. In this work the descriptions are only two pages long.

Dave was a student of Benjamin Bloom’s at the University of Chicago. He identified 5 levels of skills: imitation, manipulation, precision, articulation and naturalization.

| Dave’s Levels |

| Imitation – Students observe and copy the actions of someone else. Sample Verbs: copy, follow, mimic, repeat, replicate, reproduce |

| Manipulation – Students perform by memory or by following instructions. Skills are guided or practiced under direction. Sample Verbs: act, build, execute, implement, perform, recreate |

| Precision – Students’ skills are practiced and performed with some accuracy at independent levels and without specified directions. Sample Verbs: calibrate, complete, control, demonstrate, execute, master, perfect |

| Articulation– Students can combine two or more skills and perform consistently. Mastery is achieved. Sample Verbs: adapt, combine, coordinate, create, develop, integrate, modify |

| Naturalization – Students achieve a high performance level. They are capable of combining two or more skills in combinations. Physical skills are not only mastered but generally automatic and preformed spontaneously. Sample Verbs: design, develop, invent |

Dave, R.H. (1970 / 1975?) “Psychomotor levels” pp.33-34 in Developing and Writing Behavioural Objectives (R J Armstrong, ed.) (Tucson, Arizona, USA; Educational Innovators Press)

Resources: As applied to Dave’s Taxonomy, here is a list of non-segregated action verbs that can pertain to the psychomotor domain. Unlike most taxonomic listings, this page is listed in reverse order, from more complex to simpler categories.

Notes and reminders: Before I leave this discussion of the three classic taxonomies of learning, I want to remind readers that the strength in knowing and using these classic domains lies in their ability to help educators at all levels in creating lessons that meet a variety of learner needs and modalities. Combining domains also allows educators to create lessons that are more holistic in nature.

Too, at the risk of being repetitive, I wish to strongly remind readers that the Cognitive Domain was revised and should be reviewed for changes as it is much more correct and powerful than the original work as described here by Bloom, et. al. in 1956. Indeed, the 2001 revisions take into consideration many of the weaknesses and critiques Bloom leveled at his own work after it was published.

Samples of Holistic Lesson Plans using all 3 Traditional Domains

The following plans were created by my undergraduate students between 2002-2008 incorporating all three domains. You can view the progression in this companion PPT. Even if they are not in a subject area you are interested in, the formats can serve as a prototype.

Newer Taxonomies of Learning:

Reviewing the three major domain specific taxonomies of learning is not the end of this discussion! Before I leave this topic I wanted to bring readers’ attentions to others’ very considerable efforts in exploring how humans learn and retain information and new skills. As a bit of a tease as to what might be discovered if one was inclined to venture away from the standard taxonomies of learning, I wanted to direct readers’ attentions to two popular examples – the works of three men – Grant Wiggins and Jay McTighe (2005); and L. Dee Fink (2003). All three men have investigated how humans learn and retain information, and how to best create and organize instruction so it is memorable. Their works are much too extensive to describe fully here, but I wanted to introduce readers to these individuals in hopes that they might be intrigued enough to investigate them on their own. Additionally, I personally have implemented aspects of their works and found them easy to use and understand. I think they added depth to both my planning and my teaching. Too, these works added other dimensions to either my self-evaluation processes, or aided me as I went through my content, assignments, or contemplated possible course revisions.

While these are very brief discussions, I have tried to direct readers to other sites and pages that concentrate on describing both these newer taxonomies of learning further, or in hopes of leading readers to the parent works of these gentlemen so they can read their ideas in more detail. Indeed, I strongly encourage readers to explore many of the works of these gentlemen as I have found their discussions exceptional valuable in my own teaching. The authors that follow have created taxonomies that have the potential to improve the quality of instruction. Their works offer plans and justifications in great detail. In different venues and at different levels of instruction, all of these individuals have made strong cases for their methods of curriculum planning and lesson construction exceptionally well.

Wiggins and McTighe – Six Facets of Understanding – A taxonomy to promote understanding and thinking

Wiggins and McTighe’s concepts and ideas about learning developed over an extended period of time. They are the team who first conceptualized course construction and curricular development through “backwards design.” One of the elements that has been a consistent thread of their work from the beginning and one paramount in directing one’s choices in both teaching and course construction is the development of what they call “essential questions.” Here I have simply listed their taxonomy for understanding and examples of essential questions that reflect that level of thinking.

Their parent work is a comprehensive curriculum development model. The taxonomy of understanding is only a part of its entirety. And while their model is not hierarchical, their categories can provide educators with a strong framework by which to form and construct probing questions and thus increase students’ levels of engagement and deeper learning, as well as enhance their thinking and understanding. This taxonomy also sets up a strong model of inquiry for students to follow over a lifetime and in becoming informed and continually inquisitive adults.

| The Six Facets of Understanding: *These are not hierarchical |

| 1. Explain: Provide thorough and justifiable accounts of phenomena, facts, and data. |

| Explanation: Essential Question – How does conflict lead to change? |

| 2. Interpret: Tell meaningful stories, offer apt translations, provide a revealing historical or personal dimension to ideas and events; make subjects personal or accessible through images, anecdotes, analogies, and models. |

| Interpretation: Essential Question – How does conflict influence a person’s decisions and actions? |

| 3. Apply: Effectively use and adapt what they know in diverse contexts. |

| Application: Essential Question – What problem-solving strategies can people use to manage conflict and change? |

| 4. Have perspective: See and hear points of view through critical eyes and ears; see the big picture. |

| Perspective: Essential Question – How does a person’s point of view affect how they deal with conflict or change? |

| 5. Empathize: Find value in what others might find odd, alien, or implausible; perceive sensitively on the basis of prior indirect experience. |

| Empathy: Essential Question: How might it feel to live through a conflict that disrupts your way of life? |

| 6. Have self-knowledge: Perceive the personal style, prejudices, projections, and habits of mind that both shape and impede our own understanding; they are aware of what they do not understand and why understanding is so hard. |

| Self-Knowledge: Essential Question – What personal qualities have helped you to deal with conflict and change? |

Table 6: Wiggins and McTighe – Understanding by design – Facets of understanding – Modified from – http://www.greece.k12.ny.us/instruction/ela/6-12/BackwardDesign/BDstep1.htm (hyperlink now inactive)

To learn more about how this “taxonomy for understanding” fits into Wiggins and McTighe’s larger conceptual framework for teaching today’s students, I strongly encourage readers to investigate their concepts of backwards course design, essential questions, and their seminal framework Understanding by Design. #ad

The Taxonomy of Significant Learning

The next taxonomy of learning I want to introduce was created by L. Dee Fink. He was a college professor in the College of Liberal Arts at the University of Oklahoma. While there he went on to create and become the director of the Instructional Development Center at his university – a position he held for 26 years. He now does periodic consultancies.

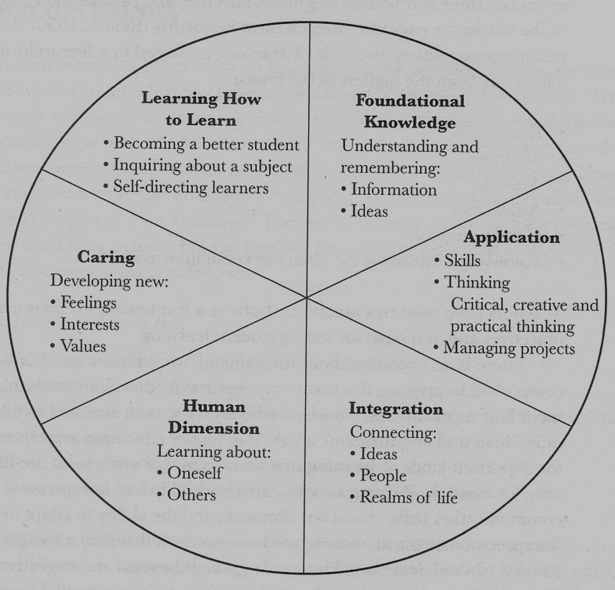

I wanted to include Dr. Fink’s taxonomy because it is highly integrative, and is one that actively combines and uses elements of cognition with aspects from the affect to create a non-hierarchical powerful taxonomy. I have used this one in creating both face-to-face and online learning segments and personally like it because it weaves together more than one domain of learning. It also allows for educator’s self-reflection and self-assessment as one looks back at instructional episodes to ascertain if they were effective. While Fink’s taxonomy was initially created for educators in higher education, I think it has promise and can be used by teachers from upper elementary through high school,

Here are the key components of the Taxonomy of Significant Learning: (Remember this is not a hierarchy.)

| Foundational Knowledge – Information & ideas |

| Refers to student’s abilities to understand and remember specific information. This stage provides basic understanding as a foundation of other kinds of learning. |

| Application – Skills, thinking, managing projects |

| Engaging in different types of thinking, action, or developing skills. This allows learning to become useful. |

| Integration – Connecting ideas, people, realms |

| The ability to see, understand, and make connections between skills, processes, thinking, and information so that a new kind of intellectual power emerges. |

| Human Dimension – Inter and intra personal knowledge |

| Heightened learning attached to personal or social implications feeds both self-esteem and self-image. This dimension informs students about the human significance of what they are learning. |

| Caring – Developing feelings, interests, values |

| Learning something new can effect how students feel about something and they are more motivated or interested in learning about it. |

| Learning How to Learn – Metacognition, thinking about one’s thinking |

| Like other’s taxonomies, this portion deals with learning how to learn, thinking about one’s thinking and retention patters, or having students investigate and become aware of how they learn best. This aspect enables continue learning and apply those skills to new tasks. |

Adapted from: Fink, L. D. (2003, 2013) Creating significant learning experiences. San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass. #ad

Developers, authors, users of varied taxonomies of learning seem very fond of placing their works in some sort of geometric representation configuration or chart. Here Fink’s condensed Taxonomy of Significant Learning has been placed in a circle, perhaps emphasizing the non-hierarchical nature of this model.

San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass.

Endings and A Personal Example:

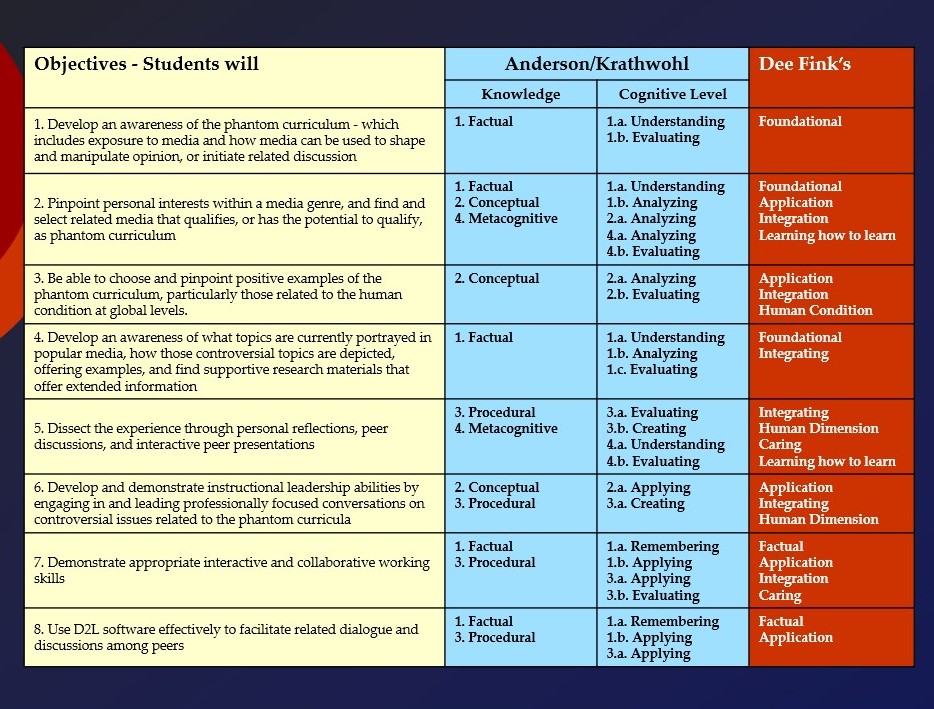

The following is an illustration of my using Fink’s taxonomy, in addition to the new revisions of Bloom’s Taxonomy from Anderson and Krathwohl. This example was an assignment given to my undergraduate Educational Psychology class – ED 381, as they were directed to explored the impact of both phantom and electronic curricula on students’ social and emotional learning.

As I evaluated students’ reflections, comments, and final products for this this assignment, using these taxonomies not only allowed me to assess whether my objectives were met, but also provided me with a visual reminder of how the assignment was constructed. From this array I could determine if I had provided opportunities for deeper learning at more personal levels. It also helped me assess the assignment for balance and meaning in the context of the entirety of the course content.

In the end, the power of learning taxonomies is that they are professional tools and they allow educators at any level to make sure he/she is providing students with the best comprehensive learning opportunities — ones that are both balanced and memorable.

General References:

Bloom, B.S. and Krathwohl, D. R. (1956) Taxonomy of Educational Objectives: The Classification of Educational Goals, by a committee of college and university examiners. Handbook I: Cognitive Domain. NY, NY: Longmans, Green.

Dave, R. (1967) “Psychomotor domain”. (Berlin: International Conference of Educational Testing).

Ingenkamp, K.H. (ed.) (1969) Developments in Educational Testing vol.1 (University of London Press, London)

Dave, R.H. (1970 / 1975?) “Psychomotor levels” pp.33-34 in Developing and Writing Behavioural Objectives (R J Armstrong, ed.) (Tucson, Arizona, USA; Educational Innovators Press)

Fink, L. D. (2003, 2013) Creating significant learning experiences. San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass. #ad

Harrow, A. (1972) A Taxonomy of Psychomotor Domain: A Guide for Developing Behavioral Objectives. New York: David McKay. #ad

Simpson E.J. (1972). The Classification of Educational Objectives in the Psychomotor Domain. Washington, DC: Gryphon House.

Wiggins, G. and McTighe, J. (2005) Understanding by Design, 2nd edition. Alexandria, VA: ASCD – (Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development) #ad